Avoiding exploitation by “faux-professionals”and “working-amateurs”by Joe PuenteFounder/President

Utah Filmmakers™ Association

While no one can claim pure objectivity, the author’s commitment to expanding the overlap between the local film Community and Utah’s film industry has required honest self-reflection and a critical—even humbling—assessment of their own place in the professional landscape. Being in what they describe as an industry-adjacent position has provided a unique perspective.

It should also be noted that novice filmmakers—those transitioning from amateurs to professionals—may find themselves in a position where the professional goal to “Get it right!” runs into the financial obstacles that amateurs often dismiss to “Just get it done!”

Put simply, they don’t have the resources to pay standard rates to cast and crew for a project. The amateur philosophy that encourages cutting corners wherever possible can form habits that are difficult to break, negatively affect the quality of one’s work, and seriously impede one’s career prospects. This doesn’t mean that there aren’t solutions one can turn to without compromising one’s commitment to professionalism.

Many novices cut their teeth on producing short films, but there are right and wrong ways to go about it. Knowing the difference separates novices on track to becoming working professionals from perpetual amateurs who might work really hard but never get very far.

Regardless of the art form, every creative Community has its share of “locally famous amateurs.” Described in this article as “faux-professionals”—“faux-,” meaning, “...imitation... not genuine; fake or false.”

Editorial note: Previous versions of this essay used the prefix “quasi-,” meaning “...apparently but not really.” While the author feels that definition is more apt in context, “faux-” meets the same descriptive requirements, is more broadly recognized, and lends itself to the abbreviated phrase “faux-pro” to hilarious effect—at least in the author’s opinion.

Faux-professionals are always working on a new project and ensuring everyone knows about it as they promote their most recent title. Incorporating just enough business terminology and trade-specific vernacular to convince those in their immediate orbit—including themselves—that they’re “in the industry.”

They’re very good at getting people excited about what they’re doing and attracting others into their bubble, especially other amateurs-turned-adulators—Community members who, perhaps, don’t produce as much and just want to “collaborate,” hoping that the charisma and ceaseless self-promotion they’re confusing for success will somehow jumpstart their own careers.

The faux-professional’s compulsive need to keep wearing all the hats blinds them—and their adulators—to conflicts of interest that are obvious to those outside of their amateur bubble, in which it’s okay to be the filmmaker and the casting director and the talent agent. Anyone who says otherwise may risk being labeled “toxic” and/or “black-listed.” Because the faux-pro’s bubble is a “safe space”—for them. A place where they don’t have to deal with the “drama” (dissenting opinions, industry norms, labor laws, etc.) or “negativity” (realistic assessments) of “bullies” and “gatekeepers” (actual professionals).

That’s just one reason why quasi-professionals are rarely at a loss for willing participants to “help” with their projects. Many of their adulators—who may prefer to think of themselves as “colleagues”—may be just as talented, if not more so, but considerably less prolific, lack confidence, and usually forget that the length of one’s resume cannot accurately gauge talent or skill. Adulators quickly forgive the faux-pro for having to work for “deferred” wages. Often convincing themselves that it’s an “honor” just to be able to “work” with them because now they think they’ve “got their foot in the door.” One can’t risk squandering that kind of “access” by fretting over things like fair compensation for services rendered. Faux-pros have a vague understanding of sacrificing for one’s art—the amateur philosophy they’ve embraced to “Just get it done!” gets easier once they figure out how to get other people to make sacrifices for them, usually by associating it with a better chance for a paycheck on “the next one.”

This is the nature of the amateur bubble. Where desperation is preyed upon, unpaid labor is repackaged as an “opportunity for experience” or a chance to do the faux-pro a “favor.” Where wage theft is called “paying your dues,” and paychecks are for “sell-outs”—unless it’s from one’s day job. Where adulators are manipulated into believing that someday they’ll be able to make their living “doing what they love,” just like the faux-professional, who always seems to scrape together just enough of an income—mostly from working on the productions of others—to pay their own bills and fund most of their next “passion project,” for which salaries will, once again, be deferred. Many of those trapped within the amateur bubble's safe confines believe there is no such thing as exploitation as long as they’re “not in it for the money.”

They fail to understand that “passion projects” are not unpaid; they are self-financed—as in, “The studio wouldn’t back my project, but I’m so passionate about it that I will hire the cast and crew with money from my own pocket.”

To be fair, some of these faux-pros—despite their unwillingness to let go of amateur thinking—do manage to carve out something resembling a “career” on the outer edges of a niche or grey market. They call it “working in the industry”—a statement that may be considered technically accurate in the same way that a self-published author is still, technically, a published author.

Success for the faux-professional is typically measured anecdotally. Some of their work may reach a slightly wider audience—even amateurs get lucky occasionally, especially when focusing more on quantity than quality. Distribution is limited to less-than-reputable options, but it’s still technically distribution. Any revenue it might generate will be piecemeal, trickling in so slowly that most of the cast and crew are likely to forget about their deferred salaries—regardless of whether or not they signed a written contract or if the project manages to break even… assuming that anyone apart from the faux-professional is in a position to know. That won’t stop their adulators from telling all their family and friends about it. “Watch it today on [a streaming platform no one has heard of]”—perhaps represented in the final budget as an empty line-item labeled “Marketing = (social media/viral?)”— providing plenty of “exposure” for “A film by [insert name of faux auteur]” who’s already “hard at work” on their next screenplay.

Exploitative bubbles are not difficult to recognize. They usually surround an individual or a small group of cohorts. They can also be found within the industry. Ostensible “Professionals” with established careers that still think like amateurs with the “Just get it done!” philosophy. Herein, they are referred to as “working-amateurs.”

What’s especially unfortunate about “working-amateurs” is that they can cloud the distinction between the Industry and the Community when they exploit Community members. This is typically in the form of wage theft. While some stoop to utilizing unpaid labor, most simply pay unfair wages. Some go even further by misclassifying employees as contractors or paying lower-level workers in cash, skirting tax laws as business owners, and making accurate income reporting much more difficult for the people they hire.

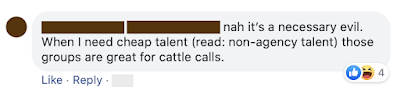

Such practices aren’t just informed by amateur thinking; they’re often justified by a scarcity mentality rooted in a need for control. It’s not that the working-amateurs don’t know any better because they often do, but they may not recognize the bridge between Community and Industry. They may feel that, having found “the door” into the Industry now that they’re in, they embrace an attitude that considers those outside their sphere of influence as “less than” the professionals they believe themselves to be—“not real filmmakers” or “not in the industry.” Their definition of “professional” may even be limited to the fact that it’s how they make their living. As noted before, this can be very discouraging to Community members that want to work in the Industry, especially when working-amateurs show their true colors within Community forums.

|

| A working-amateur derides online community forums they participate in and/or manage through social media. |

Ironically, such derision shown to the Community doesn’t prevent working-amateurs and faux-professionals from using the same tools and the language of established Industry and Community resources to try and mimic them for their own purposes.

Anyone can use the critical and practical tools discussed previously to determine if something presented as a resource for the “community” is legitimate or not—especially if it appears redundant and cliquey. Genuine altruistic endeavors will stand up to scrutiny and satisfactorily answer important questions:

For what purpose was it established?

Does it try to reinvent or supplant something that already exists?

Was there a previous affiliation with an established resource/organization?

If that affiliation has been severed, why?

If that affiliation has NOT been severed, why?

Does it present itself as a magnanimous undertaking?

Is it actively collecting personal and professional information?

If so, to what end?

(Directories are usually publicly accessible resources; databases and contact lists, typically, are not.)

Is it selling something available elsewhere for free or already provided by a different, established resource?

Are they offering “classes” or “Workshops”?

Are they hosting experienced instructors or teaching everything themselves?

Is it seeking donations?

Does it claim to be an accepting community while behaving as an exclusive club of like-minded members?

Does it set realistic expectations or emphasize affirmation, encouragement, and positivity?

Do they value honest critique, or do they prefer coddling?

Do they go a little overboard with the familial and/or sports metaphors?

Do they claim to be “a family?”

Do they talk a lot about their “team?”

Does it take the industry seriously and acknowledge economic reality, or does it sidestep those topics to emphasize “passion” and the “art form?”

Are those behind it being direct and transparent about their motivations, efforts, and intentions?

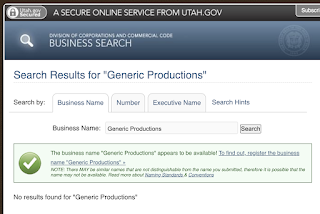

Or does access to that information require one to do some digital digging?

Many of these questions can be answered through publicly available sources. Those answers may validate or disprove what is being presented. They may also expose unethical or illegal practices.

When financial support is solicited through direct “donations,” crowdfunding, or membership platforms, it’s important to remember that anyone can create profiles with such services, and not all contributions are tax-deductible.

Membership platforms are ineffective for financing unproven concepts. They exist for established creators who produce content regularly and know how to monetize it. There are no shortcuts to doing the work.

Projects with no expectation of a return on investment should never be described as “nonprofit” undertakings—though it does happen. “Nonprofit” is a term often associated—but not synonymous—with “tax-exempt” status, but tax-exempt organizations are not allowed to request donations without a solicitations permit!

Faux-professionals often fail to understand that operating a business at a loss differs greatly from running a nonprofit organization. For example, business losses can only be claimed on federal income taxes for three out of five years. Working on a film set in any capacity without being paid cannot be legally classified as “volunteer” work. Anyone convinced to “donate” their time and talent to a project is not “helping” the production; they are allowing themselves to be complicit in their own exploitation and undermining the value of the work for others.

Still, if it’s promoted as something that aims to benefit a community, creating a public impression of altruism, it probably should not be operated by anyone who could financially benefit from what it claims to offer—regardless of whether or not it’s profitable. It’s still a conflict of interest; faux-professionals and pro-amateurs may fail to see that or find a way to justify it. It may appear to yield advantages or small gains in the short term, but only at the expense of other amateurs. Still, it will not go unnoticed by actual professionals for the maladroit distraction that it is.

| The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors and—especially where guest posts are concerned—do not necessarily reflect the official policies and/or practice of the Utah Filmmakers™ Association, its officers and/or associates. |